During the 1850s, Swiss lake levels hit a 200-year record low, which revealed the remains of prehistoric pile-dwelling settlements.

This discovery created a surge of interest in the Swiss Neolithic now known as, “Pfahlbaufieber” (“Pile Dwelling Fever”). Local residents, called “Pfahlbaufischer” (“pile-dwelling fishers”), sought to capitalize on the popularity of these new discoveries by “fishing” cultural remains out of the shallow waters from boats using long poles. These items were then sold to tourists, dealers, museums, and other interested parties.

As the pile-dwellings sites gained international popularity, many of the artifacts were sold to individuals and museums abroad. This “artifact diaspora” explains the current, worldwide distribution of Swiss lake-dwelling material.

Key Players

The site of Robenhausen was discovered in the winter of 1853-54 by a farmer named Jakob Messikommer. As a farmer, Messikommer was interested in not only the artifacts, but also the plants and other organic remains associated with them. It is largely due to his approach that the well-preserved organic material present at this site was not simply discarded, as was common practice at the time. Throughout the course of his excavations, Messikommer was in close contact with Ferdinand Keller, the head of the newly-formed Antiquarische Gesellschaft in Zürich (Antiquarian Society in Zurich). Keller published a number of articles and monographs on lake dwelling sites, or stations, as they are called in Switzerland. Several of these were translated for English-speaking audiences, the most important of which was The Lake Dwellings of Switzerland (1866). Messikommer also consulted with Oswald Heer and Ludwig Rütimeyer, a botanist and faunal expert respectively, concerning the plant and animal remains found at the site.

While Messikommer’s excavations do not compare to modern systematic standards, his methods were nevertheless more precise than those of his contemporaries. Although his lack of skill in drawing resulted in few artifact sketches or excavation plans being made of the site, Messikommer was remarkably meticulous in preserving and examining the organic remains unearthed at Robenhausen. He developed the earliest recorded system of water floatation for retrieving botanical remains, among other innovations. Many of these items were sold, and the proceeds used to continue funding excavation efforts. Before selling these items, Messikommer affixed a label bearing the site name and his own. Since Messikommer’s label style changed gradually throughout over several decades, modern researchers have constructed a chronology to roughly date individual items based on label style (Figure 15).

Figure 15: A15008 Example of original Messikommer label.

This, in turn, makes it possible to approximate the original find location of various objects, based on where Messikommer was excavating in a given year. In addition to selling items, Messikommer also opened the site for tours and kept a guest book to record his visitors. His work at Robenhausen helped lay the groundwork for modern, systematic archaeological and bioarchaeological investigation.

Jakob Messikommer’s son, Heinrich, published an overview of excavations at the site entitled Die Pfahlbauten von Robenhausen (The Pile Dwellings of Robenhausen). By the time of this publication (1913), many of the artifacts had left the country due to the “Pfahlbaufieber” (pile-dwelling fever) phenomenon.

MPM Involvement

The Milwaukee Public Museum’s Swiss Neolithic collection was accessioned and catalogued throughout the late 19th and early 20th century. Many of the items in the collection were donated by early supporters or employees of the museum. Since collecting various items while traveling was a popular practice at the time, many of the items in the MPM collection were acquired abroad and stored in private collections before being donated or sold to the Museum.

Charles Doerflinger

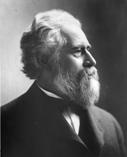

Figure 16 Photo of C. Doerflinger, first Custodian of the MPM. MPM negative #123203

Charles Doerflinger is perhaps the best known of these donors. A first-generation German immigrant, Doerflinger was wounded while fighting at Chancellorsville, Virginia during the Civil War. His left leg was amputated above the knee, and it continued to pain him throughout his life. After the war, he served as the first director (custodian) and curator of the Milwaukee Public Museum. When chronic pain forced him to resign in 1887, he traveled to Europe, intending to “take the cure” at world-famous spas.

Doerflinger and his family lived in Zürich for a time, and his name appears in Messikommer’s site guest book, indicating that he participated in Messikommer’s excavations and acquired a number of items during his visits at Robenhausen. When Doerflinger returned to the United States, he brought these items home with him. While they were originally given to the museum on loan, Doerflinger eventually transferred ownership of 70 items to MPM in 1913.

Figure 17: Photo of Adolph Meinecke.

Adolph Meinecke

Adolph Meinecke was a first-generation German immigrant who served several terms on the Milwaukee Public Museum board, and was a close personal friend of Doerflinger. During several visits to Europe, he collected a number of archaeological specimens, 32 of which are now housed in the Swiss Neolithic collection.

Other Donors

In addition to Doerflinger and Meinecke, lake-dwelling items also came into the museum between 1901 and 1910 through Max Rosenthal, F.J. Perkins, William Frankfurth, and J.A. Renggly (also spelled Renggli). Some of these items were donated to the collections, while others were purchased by the Museum. Due to the popularity of the Swiss Lake sites, some unscrupulous dealers would “modify” artifacts in order to present them to customers as a new tool. Collectors seeking to purchase a diverse range of artifacts would be more likely to purchase this “new” or “different” item, instead of an object similar to one they already owned. While MPM records show that Renggly’s donations, sales, and contributions were appreciated, Swiss records indicate that his business practices were questionable. A number of items in the MPM collection passed through Renggly’s hands, and several examples exhibit these modern modifications, affecting the credibility of the object. Several of the lithic artifacts he sold to the MPM are, in fact, neither Neolithic in date nor from Switzerland.

Modern Innovations

Modern research methods have drastically changed the excavation and research approaches at sites like Robenhausen. Thanks to the development of systematic excavation methods, artifacts are now well-documented before they are removed from the ground. Since archaeology is a destructive process, this ensures that future researchers will be able to “examine” the site through the notes, records, photographs, and other data gathered during the original excavation. Most of the recent lake-dwelling excavations have involved contract archaeology conducted in port areas of harbors on several lakes. Examples include Zürich-Mozartstrasse and Arbon-Bleiche.

New technology has also changed how archaeologists date such sites. While carbon dating is possible at many Swiss Neolithic sites, a less destructive and more accurate method is dendrochronology, which dates sites by analyzing tree growth patterns. A tree’s growth can be measured and analyzed based on the rings that form annually within its trunk. The yearly growth of these rings is affected by local weather conditions, rainfall patterns, and other factors. Over the lifespan of the tree, these conditions form a unique growth pattern that can be compared to trees whose age is known, making it possible to date a wooden object to within a few years. In addition to the wooden artifacts preserved at Swiss Neolithic sites, many large posts used to support the wattle-and-daub homes were also preserved. These posts are ideal samples for dendrochronology, which in this part of Europe is extremely detailed and complete, especially for the lake-dwelling period of occupation.

Current Work

While the initial Pfahlbaufieber excavations in the late 19th century introduced the public to the lake dweller sites, work in the latter half of the 20th century allowed researchers to construct a clearer chronological framework. In addition to the advances in modern systematic archaeological techniques, the development of underwater archaeology has opened up new avenues of investigation for sites still located below the lake levels.

In the Milwaukee area, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Anthropology professor Dr. Bettina Arnold works with both the Swiss Neolithic and other Old world archaeology collections. A number of her graduate students, including James Johnson, Jaclyn Lillis, and Katherine Ross, have used the MPM Swiss Neolithic collection in conjunction with other assemblages as a basis for their Masters theses on topics ranging from tool use to textile production. Swiss researchers include Kurt Altorfer, whose Master’s thesis entitled, Die Prähistorischen Feuchtbodensiedlungen von Wetzikon-Robenhausen (The Prehistoric Wetland Settlements of Wetzikon-Robenhausen) was recently published (2010). Additionally, there are a number of collections, open-air museums, and other resources for examining the Swiss Neolithic. Collections in the United States can be found at the Field Museum in Chicago, the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, the Smithsonian Institution, the Yale Peabody Museum, and the Peabody Museum at Harvard. Major collections are also curated at the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology at Oxford University and the British Museum. Open-air museums in Germany and Switzerland featuring the lake-dwelling way of life include the Federseemuseum in Bad Buchau, the Pfahlbau Museum of Unteruhldingen, Pfahlbaudorf Gletterenes, and the Pfahlbaumuseum Lüscherz.

Erika Ruhl and Bettina Arnold would like to thank Kurt Altorfer and the National Museum in Zürich for access to primary documents referenced on this website.

MPM Collection

The Milwaukee Public Museum’s Swiss lake collection consists of nearly 200 items, ranging from stone, wood, and antler tools to preserved textiles and ceramics. The collection also includes an example of a wooden “pile,” which would have been used to support houses at the time. These items entered the Museum through through the activities of 12 individuals between 1901 and 1931. In recent years, this collection has served as the basis of several Masters’ and research projects, and two items from this collection can be found in the MPM “Sense of Wonder” exhibit on the first floor. The following is a sample of items from this collection. They were selected for the diagnostic features characteristic of this time period, in addition to what they reveal about life during the Swiss Neolithic.