Defined as Runners

Many translations of the Tarahumara name Rarámuri include "foot runner," "light feet," or "they who walk well." Walking and running long distances are necessary parts of life for the Tarahumara. The terrain of their homeland is filled with many foothills, deserts, gorges, and rivers -- all at a high altitude that make using pack animals very difficult. The Tarahumara find it more efficient to travel by foot (often barefoot), sometimes covering five miles just to reach the next neighboring farm. Some Tarahumara hunters will run their prey to exhaustion, rather than using bow and arrow or bullets.

Excellent runners hold a higher social standing in Tarahumara communities, and this talent crosses gender boundaries. The concept of running is instilled in boys and girls from a very young age and maintained throughout an individual’s life with competitive games such as foot races, or palillo, a game resembling lacrosse but with the intensity of rugby, which can last for days and several hundred miles. The Tarahumara are widely known by outsiders (chabochis) for their amazing ability to run long distances as observed in Olympic and Ultra-marathon circuits.

Tarahumara footraces are community affairs. Some participate in the races, others prepare food, and some are involved in betting beforehand. Kickball races called dalahípu or dalahípami are major events in Tarahumara pueblos, with preparation beginning three days prior to the actual race. The actual race consists of two teams of up to 12 men, each one having to complete the same distance as his teammates (2–12 miles) while passing a three-inch wooden ball back and forth with their feet. Usually the course is chosen for the flattest ground but often this is not possible. The runners will have to cross streams, climb hills, and hop fences, all while advancing the ball forward to teammates. The duration of each race is determined by the number of miles run; shorter races last a few hours while the longer races can last more than a day.

Women also have a version of this race called dowérami. Instead of a ball, sticks and hoops are used to progress, but the same basic rules apply.

The bet, called táli, is considered one of the most important parts of racing events. Each team has at least three tcokéame who collect bets and deal with the other team’s tcokéame (Bennett and Zingg 1935). All bets are carefully matched, taken, and stored before the race begins. What may seem to be a pastime is an essential social and cultural endeavor for the Tarahumara.

Co-Operative Labor

For centuries, money was not a driving force in the Tarahumara economy; people used and continue to use a type of bartering system to acquire many goods and services. When individuals need help on their land, workers are “hired” to perform whatever task is needed in a service called a tesgüinada. The workers are usually neighbors or a relative (sometimes both). In return for the help, the individual who benefited from the work provides food and tesgüino, a corn-based alcohol prized among the Tarahumara. In most cases if the person is wealthy and the job large, the requestor may throw a tesgüinada as repayment.

This type of co-operative labor also is used when items are in need; no Tarahumara will think twice to loan goods or services to another individual in the community. The concept of co-operative labor is so fundamental in the Tarahumara culture that a refusal of help can result in an excommunication from the community. Although there can be distinctions made between “poor” and “wealthy” based on the amount of cattle or land owned, each individual, except the shaman, is seen as having a similar social standing.

Gender Roles

In Tarahumara society, men and women are dependent upon each other to maintain their semi-nomadic, agricultural way of life. Adult roles are distinctly divided by gender, leaving each individual with only half of the skills needed to survive in the Copper Canyon. Although there are other reasons for marriage, the Tarahumara “recognize [it] and discuss marriage as an arrangement in view of the reciprocal economic needs of one sex for the other” (Bennett and Zingg 1935: 78). The marriage ceremony specifically articulates the pair “to be industrious” (Bennett and Zingg 1935: 225) and goes further to outline the duties of the couple. The woman may own land, but it is the role of her husband to cultivate it, just as the husband may own a herd of sheep but it is his wife’s duty to attend to them. One is not seen as more useful than the other but both the man and women are a part of “a contract of two economic equals” (Bennett and Zingg 1935: 232). While the ideology is strict in its assignment of gendered tasks, practicality can often overrule them. Some duties, while primarily considered a man’s, can be accomplished by his wife or children if necessary, and vice versa. For example, cattle are prized among the Tarahumara and are carefully cared for by the men in the village, but if they have prior engagements the women and children watch the herd.

Men

“The Final Touches in Violin Manufacture” from Bennett and Zingg (1935)

Courtesy of University of Chicago Press.

The duties of a man in Tarahumara society require him to work outside the home. A primary role of a Tarahumara male is to act as a lumberjack and wood worker. When the Spanish invaded the area in the 16th century, the steel axe was introduced and the dense pine and ash forests became a vast resource for the Tarahumara. The men are very skilled and create everything from dwellings and storehouses to musical instruments with little more than hand tools and a steel axe.

Another duty of a Tarahumara man, as mentioned above, is to maintain and cultivate the family fields. This includes plowing, sowing, harvesting, and preparing the land for the next planting season, not to mention guarding the fields from pesky animals. He does not always do this alone, however; it is common that his male neighbors help if needed (see Co-Operative Labor). At harvest time, the men gather their crops and travel to surrounding settlements (including Mexican) to trade or sell items. Although the women are not present during the transaction, the men consult them beforehand. A sole male occupation is that of the office of “officials,” mostly consisting of the gobernador (the leader and spokesperson of the pueblo), the capitán, the mayor, and the dopíliki.

Women

“Inserting the Design in Blanket – Weaving” from Bennett and Zingg (1930)

Courtesy of University of Chicago Press.

In the 1930s, Bennett and Zingg recognized that “the preparation of wool and the spinning of blankets is the most important and most laborious task of the Tarahumara woman” (1935:90). This included caring for the family’s herds of sheep and goats, skirting the wool, and everything in between until the product is finished. Weaving continues to be an important task, but the adaptation of Western mass-produced clothing may change this in the future.

To make a household run smoothly in the Sierra Madre is a continuous job for the Tarahumara women. Although stores are becoming more prevalent near Tarahumara territories, most everyday items are not purchased; they are often created from local materials, quite literally “homemade.” The collection, storage, and construction of materials must be done with a honed skill that has been refined since childhood. Basketry and pottery production require a finessed touch and have become more than just utilitarian; women are now selling their basketry and pottery as native folk art to the tourists who come to the area.

Cooking instruments -- metates and spoons as well as cooking vessels -- are all created by the woman of the house. Pottery production was common to Tarahumara women, but many now have modern dishes and pans. Most families have two sets of vessels; one for their summer house in the highlands, and the other for their winter cave dwellings in the barrancas.

The preparation of food and the corn based beer, tesqüino, are very important duties of Tarahumara women; both are necessary not only for everyday meals but for integral ceremonies, cures, and tesqüinadas that keep the society functioning.

Children

“The toys of Tarahumara children reflect the patterns of the culture, and their games and pastimes recreate the industries and occupations of their elders” (Bennett and Zingg 1930: 97). Children in Tarahumara society have responsibilities in the household with their mothers and in the pasture with the family’s sheep and goat herds. It is common for a child to venture far from the dwelling to take the herds to new pastures, spending days or weeks only having a dog for company. “This conditioning in childhood is largely responsible for the stolid attitude of the adult Tarahumara” (Bennett and Zingg 1930: 15). Most of what Tarahumara children do prepares them for their adult roles (thought to be reached by age 15). Toys often mimic tools that are used by either gender: model corrals, stone metates, and sling shots are used as a sort of “practice” for what is to come. While gendered duties may be completed by the opposite sex, in the child’s world the roles are very distinct and are often played out in games.

Religion – Shamanism and Christianity

Tarahumara religion combines Christian and traditional shamanistic beliefs. When the Conquistadors first encountered the Tarahumara in the 16th century they attempted to convert them to Christianity. Some Tarahumara converted (called bautizados) but did not fully adopt all aspects of the new religion. Those that do not identify themselves with the Christian church are referred to as gentiles, although there are not many distinct differences in their beliefs.

The Tarahumara shaman (oorúgame or selínowa) has multiple duties: he is a healer, a ritualist, and a protector of the old ways and the community. The shaman can be a full or part time practitioner and fulfills one or more of the following roles: a chanter (sings ceremony songs), a maggot extractor (a specialized skill that only certain shamans have), medio doctor (one who has extensive knowledge of medicinal plants), peyotero (uses the peyote plant in cures), or an assistant to one of these individuals. These skills are taught to a shaman’s successor through an apprenticeship. The role of the shaman is not an ascribed status -- bloodlines are thought to hold these abilities -- so in most cases, the successor is a son or daughter.

When the Conquistadors and missionaries entered the Sierra Madre, the Tarahumara retreated into the harsh terrain of the Canyons, but they did not escape the invaders’ influence. Over time, the Tarahumara developed a hybridized Christian and shamanistic religion. The uses of the signs of the cross, rosaries, crucifixes, the names of saints and deities, and even a mass have been accepted in this system. San José su Cristo, the Virgin Mary, and God are the saints and deities that are acknowledged by the Tarahumara, all of whom played an important role in shaping their modern world. They recognize God as one deity that embodies three people. He is credited as the creator for everything in the world and is architect and regulator of all the powers that come with it.

“Headdress, Rattle, and Fan of Matachine Dancer” from Bennett and Zingg (1935)

Courtesy of University of Chicago Press.

Matachine dancers perform for ceremonies and church fiestas.

The Tarahumara believe that all breathing things have souls (iwigála). According to the Tarahumara, the soul is what gives living beings the ability to sing and to talk. The soul has characteristics opposite to those in everyday life. If a person is cold, it means the soul is hot; and if they are asleep, the soul is awake and out working. “Night is the day of the moon; and during this day, the dead and the soul function” (Bennett and Zingg 1935: 323), this soul resides in the heart while the windpipe provides it with air and the lungs strengthen it.

Like many religions the Tarahumara hold the belief in an afterlife consisting of a Heaven and a Hell. Heaven has three planes of existence; the individual’s soul starts on the lowest plane and lives out his regular life as he did on earth until he dies and hopefully rises to the next plane. If they reach the third and final plane, they will be in the home of God himself. Hell also has three planes of existence, concluding with a consummation of fire. Before the introduction of Christianity, there was no evidence in the belief of a Hell or devil; this appears to be a more modern idea.

A History of External Influence

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Tarahumara have inhabited the Mexican state of Chihuahua for nearly 2,000 years. In the last 400 years, foreign cultures have influenced the Tarahumara. The Conquistadors and the Jesuit missionaries of the 16th century were only the beginning, as today’s Tarahumara have adopted many elements of Mexican material culture, and continually encounter the demands of ethnic tourism and a booming narcotics industry.

The Spanish and the Jesuits

The Conquistador’s goal was to conquer and colonize the land in the name of the Spanish monarchy. The impact on the native people was devastating until the Law of Burgos was passed (1512), prohibiting the maltreatment of the indigenous people in favor of encouraging conversion to Catholicism. When the Spanish worked their way inland towards Tarahumara homelands, the group fought and then slowly retreated farther into the highlands of the Copper Canyon, hoping to avoid contact with the foreign chabochis. The rugged terrain kept the Conquistadors from pursuing for some time, but the Jesuit missionaries slowly worked their way into the Canyon.

The Copper Canyon in the Sierra Madre Occidental; home of the Tarahumara.

Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Although little is known about the Tarahumara prior to Jesuit contact, their influences can be felt and seen in modern Tarahumara society. Even the name “Tarahumara” is a by-product of Spanish influence, originally used by the missionaries to refer to the converted Indians but is now used worldwide for all Rarámuri people (Baron 2008). Ideologies shifted and were molded by the missionaries (see Religion), bringing about new associations and groupings. There was a divide between the gentiles and the converted, and the two sides limited their interaction with each other. Pueblos became both physically and spiritually focused on the church.

Once the Spanish discovered gold and silver at Parral, Chihuahua, Mexico in 1631, they advanced into the Copper Canyon bringing more technology from the motherland. Many new items were introduced, including the steel axe and domesticated animals (cattle, sheep, goats, horses, burros, mules, and pigs). While the Tarahumara had presumably depended on hunting and gathering in the forested Canyon before Spanish contact, their lives were transformed by farming and animal husbandry. Until recently, cattle, sheep, and goats have been the only providers of the manure that fertilizes crops, the wool for clothing, and the little protein that make up the Tarahumara diet.

Musical instruments such as the violin, guitar, drum, and flute were also integrated into Tarahumara culture. Documentation of instruments that closely resembled the violin (similar to a Jew’s harp) existed before Spanish arrival, but by the time research was conducted, violins were fully assimilated into the culture.

During the mid-18th century, friction between the Jesuits and the Inquisition and the new king Carlos III (1760) resulted in the expulsion of the Jesuits from Spain and all Spanish territories. After many rumors of the wealth and power that the Jesuits had acquired in the New World, the missionaries were also expelled from Tarahumara land in 1767, thus removing immediate external pressures until the modern era (McChesney 2007).

Modern Influences

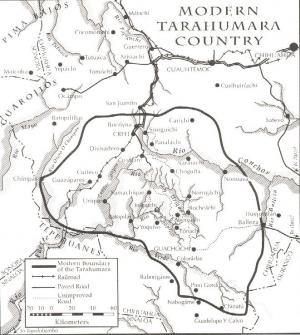

Map of present-day Tarahumara territory.Courtesy of questconnect.org.

In 1821, when Mexico won its independence from Spain, the new government encouraged citizens to move farther into the Chihuahua territory. This resulted in the Tarahumara retreating further into the Copper Canyon. From that time the Mexican government, miners, lumber yards, tourists and, most recently, drug wars have plagued the indigenous canyon dwellers.

When chabochis moved into Tarahumara territory they brought with them new trade industries, primarily mining. In 1856, communal land ownership was outlawed by the Finance Minister, Miguel Lerdo de Tejada, by passing the Lerdo Law, which freed more land for the new settlers deep within the Sierra Madre. During the 1870s, Mexican mining boomed; gold, silver, and copper were found in the major rivers that make up the Sierra Madre and the new citizens took advantage of it (Anderson 1996). The Tarahumara were exploited as a cheap labor source for the mining and the upland timber industry. This led the Tarahumara to further retreat into the canyons, but this did not prevent some of the indigenous populations were “Mexicanized.” Some learned how to speak Spanish, while others took on Mexican clothing styles such as palm leaf hats, cotton skirts, and the infamous guaraches (tire or leather shoes).

In the 1900s, Jesuits re-entered Mexico and expanded upon their old territories by establishing orphanages, hospitals, and clinics for the Tarahumara. However, during the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), the land that was acquired by the Jesuits and a small percentage of what was taken in 1856 was given back to the tribe. The Tarahumara territory is now approximately 50,000 square miles –- half of what it was before European contact (Baron 2008).

Contemporary Western influences have brought fast food (chatarra) to the traditional diet of corn and beans. Potato chips, Coca Cola, and Tecate beer cans are bought with the money that is received from the “folk art” (wood carvings and dolls, textiles, pottery, and basketry) sold to tourists. Men and women are also abandoning the cotton clothing styles introduced by the Spanish for denim jeans.

The recent threat of marijuana and heroin traffickers has had a major impact on the Tarahumara lifestyle. The drug traffickers, mostly of opium and marijuana, are encroaching on the Tarahumara’s crop fields and taking advantage of the isolation to run an unlimited supply of drugs and money through the region. Tarahumara are also recruited to work the fields. The pay from this industry is significantly greater than what can be made selling tourist goods, and Western ideals focused on money and prestige are becoming more apparent among subsequent generations of Tarahumara youth.

The Mexican government is also pressuring the Tarahumara to change; new economic development in the area is being encouraged to combat the illegal activity. It is hoped that more development and police presence will stop or severely limit the drug trade. This development would involve substantial alterations to Tarahumara homelands and would inevitably cause a clash of cultures. The future of the Tarahumara remains ever-changing.