Cosmic Curiosities

"Summer night – even the stars are whispering to each other."

- Kobayashi Issa, Japanese poet

Aurora, Anyone?

The aurora is a wondrous sight to behold! In Wisconsin, we often call this the “northern lights.”

I was very fortunate to observe this sky-spectacular back on April 23, 2023. I had not seen them so bright since way back in 2001—22 years ago. The northern lights were actually shining all across the sky—high above and to the south. The photo above was a 4-second exposure. Notice the stars of the Big Dipper.

Many other sky-watchers across Wisconsin and the upper Midwest saw the dancing lights, too! However, it is estimated less than 5% of the world’s population has witnessed these pulsing lights. Perhaps you are a member of this small group? Or maybe you keep hearing about them and want to see them for yourself.

To increase your chances of experiencing the aurora, you can join the Great Lakes Aurora Hunters Facebook group. Also, aurora predictions and updates can be found at Space Weather.

WHAT CAUSES THE AURORA?

Sun storms trigger the aurora. More opportunities are coming in the next few years to see the northern lights because solar storms are increasing. Around every 11 years, the sun's magnetic cycle ramps up. The peak arrives in 2025; this solar maximum is better known as solar max.

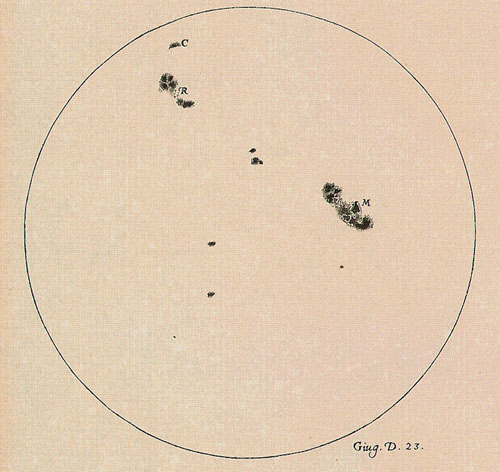

During the time of solar max, the sun's magnetic poles flip. These changes in our star’s magnetism produce a greater number of sunspots. These are energy centers that cause solar eruptions. Solar minimum—back around 2014—had little sunspot activity.

When astronomers see more sunspots, they know the potential for solar flares increases. Still, they can’t predict exactly when this eruption might occur. In addition, they do not know exactly the reason behind the sun’s magnetic cycle—why 11 years and not some other number.

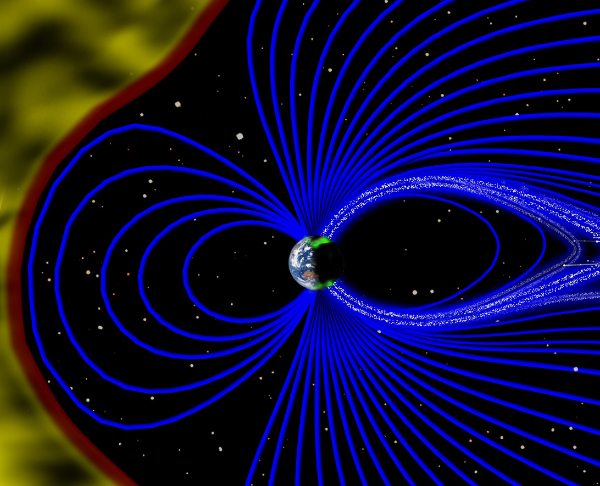

Any solar blast releases numerous charged particles, mainly protons and electrons. The particles travel extremely quickly, but still take a day or two to reach the Earth. If the storm is strong enough—and aimed at the Earth—we might have aurora in a night or two. This means we have advanced warning when there’s a good chance for aurora pulsing in our night sky. But there are no guarantees; aurora predictions can be fickle.

When the charged particles from the sun arrive at Earth, they mostly get deflected by Earth’s magnetic field. Many, however, circle back toward the Earth as they get caught in the magnetic field lines where they spiral down toward the north and south magnetic poles. On their way, the sun particles smash into the Earth’s atmosphere. These collisions – with countless nitrogen and oxygen atoms in our upper atmosphere – give us the electric glow of the aurora.

Scientists have measured the number of sunspots in detail ever since the telescope was invented about 400 years ago. Galileo was one of the first to sketch sunspots—but, of course, he did not know they caused the aurora. A strange twist to this story happened when Galileo named the unusual lights "aurora borealis" after Aurora, the Roman goddess of morning: His explanation for the aurora was not correct; he reasoned their cause was due to sunlight reflecting from the atmosphere.

The peak intensity for solar max varies each time. It’s difficult to predict exactly how many auroras we will have this time around, but stay tuned and hopefully we’ll have more stunning views of this incredible sky-sight!

Moon Mania!

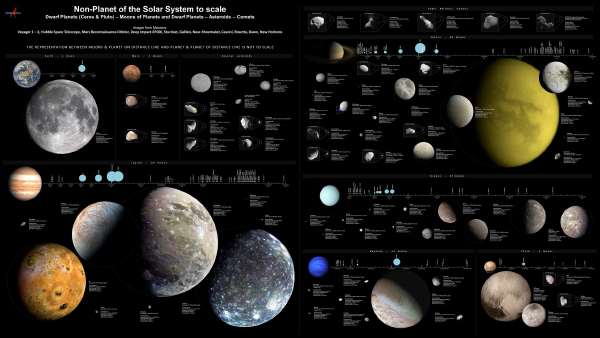

The number of known moons in our solar system has always been changing. For countless years, there was only one—our Earth’s lovely partner. Our moon’s changing face—or phase—never fails to catch the human eye.

In 1610, things changed drastically with the big eye of the new telescope. Galileo saw four moons going around Jupiter in 1610—proving not everything in the heavens circled the Earth. In 1655, Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens discovered Titan, Saturn's largest moon. Three hundred years later—around 1970—the number of known moons stood at 32.

Click to enlarge image

Lately, the number has been exploding. A year ago in 2022, the moon total increased to 220. Today, we are at 296!

Recently, researchers spotted 12 moons orbiting Jupiter, pushing its new total to 95. Shortly after that, they discovered 62 more moons orbiting Saturn—giving it 145 total moons, and the lead!

The new objects are pretty small—most are only 1-2 miles in size. They are oddly shaped, not circular like our moon. You have to be about 500 miles across to have enough gravity to pull yourself into a ball. These new moons are shaped more like potatoes, or common small rocks you might find on the ground here on Earth.

Saturn’s new moons are far away, orbiting between 6 and 18 million miles away. Most of Saturn’s moons are located within a million miles of the gas giant. The 62 new moons could be debris from bigger moons that were torn apart by Saturn’s tidal forces. Saturn’s beautiful rings are theorized to have formed this way.

I imagine the planet battle for moon supremacy will continue between Jupiter and Saturn!

A New, Distant Supernova

About 21 million years ago, a star ran out of fuel. It then detonated as a supernova.

Less than a week ago (I’m writing this on May 22, 2023), Japanese Astronomer Koichi Itagaki witnessed the light from this distant explosion. Even light speed seems slow sometimes.

The supernova, called SN 2023ixf, is located in the very picturesque Pinwheel Galaxy, or M101. It is the closest supernova seen in the past five years and the second supernova found in M101 in the past 15 years. This is a Type II supernova, an explosion that occurs after a massive star has built up a dense iron core and thus, has run out of fuel. It collapses upon itself and rebounds into its fiery death.

In our night sky, the galaxy is located in Ursa Major, the Great Bear. You need a fairly good telescope to see it with your own eyes. It is shining at about 11 magnitude. It should be visible for weeks, maybe even a few months.

Space in Sixty Seconds

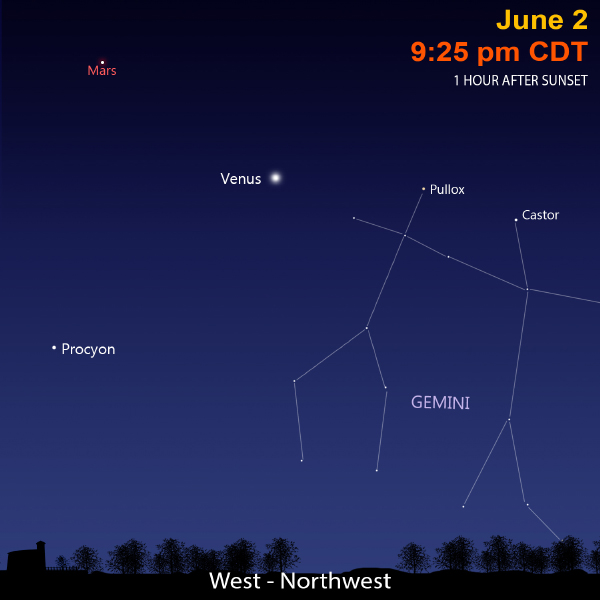

Catch the planets — and a bowling pin — in the June sky!

Sky Sights

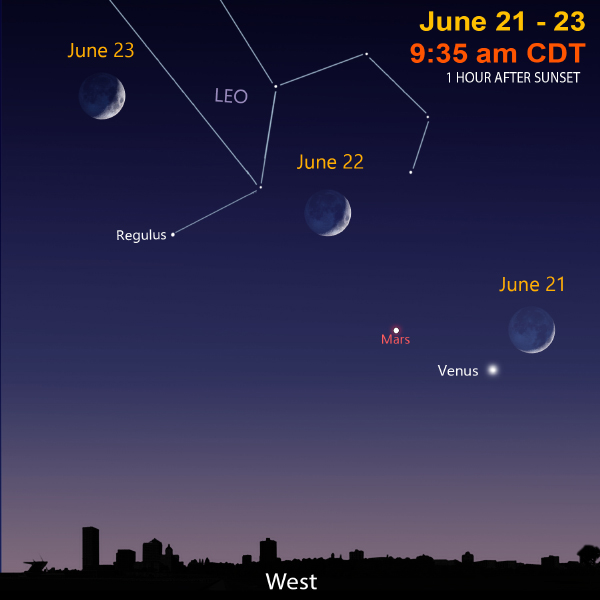

Venus and Mars set a little earlier after sunset, but are still seen easily in the western sky. Reddish Mars and crazy-bright Venus are joined by a young crescent Moon from June 21-23.

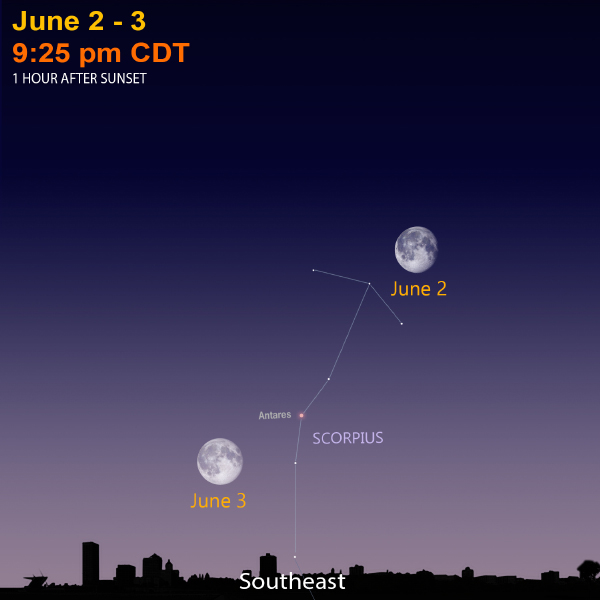

June 3, the Strawberry Moon pairs up with the red giant star Antares in Scorpius. June’s full moon gets this name because this month, strawberries are ripe for picking. Other names for June’s full moon are honey, mead, rose, green corn, hot, and thunder.

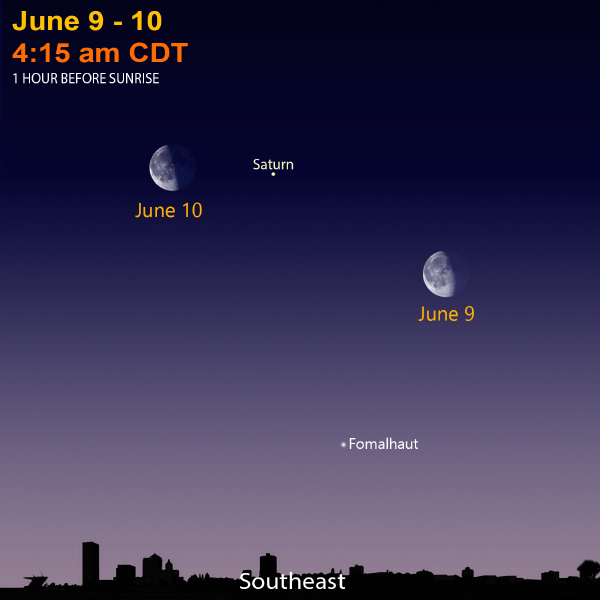

Saturn moves into the evening sky at the end of the month—barely. On June 1, the ring jewel rises at 1:30 a.m. By June 30, it rises two hours earlier at 11:30 p.m. The Moon passes by from June 9-10.

Jupiter rises about 1.5 hours before sunrise on June 1 and just over three hours by month’s end. Watch the Moon shine nearby June 13-15 in the constellation of Aries the Ram.

Mercury will be nearly impossible to spot without binoculars or a telescope in the very early morning sky.

June Star Map

Sign Up

Receive this newsletter via email!

Subscribe

See the Universe through a telescope

Join one of the Milwaukee-area astronomy clubs and spot craters on the Moon, the rings of Saturn, the moons of Jupiter, and much more.

Follow Bob on social media

Twitter: @MPMPlanetarium

Facebook: Daniel M. Soref Planetarium