Cosmic Curiosities

“How can I hope to be friends with the hard white stars whose flaring and hissing are not speech but pure radiance?”

- Mary Oliver, American Poet

Stellar Speedway

Here at the Daniel M. Soref Planetarium, when we speed up time to show how the stars change through the night, we often proclaim that the stars are not moving above you; it is the Earth spinning below your feet. Well, that’s partly true; the Earth does rotate very quickly, but the stars move even faster!

Stars are huge balls of hydrogen, mostly. Billions and billions whirl around the core of the Milky Way. We are located 27 lightyears from the galaxy’s center, so the stars in our sky speed along at around 150 miles per second. Though racing rapidly, they still take about 230 million years to make one orbit around our galaxy.

Galactic stars do not move perfectly together in one great cosmic circle. They have random motions. Notice that the stars of the Big Dipper move more than 200,000 years in the video. The dates run from 100,000 BC to 100,000 AD. Long ago and far into the future, the Big Dipper will not look like a Big Dipper!

We do not observe this speedy motion simply because our lifetimes are comparatively short, and the stars are extremely faraway. How far? The closest star of the Dipper is Megrez at 58 lightyears away, or 350 trillion miles. With present technology, our fastest spaceship travels at 10 miles per second. At that speed, it would take more than a million years to reach Megrez!

Conversely, imagine a car speeding past you a block away at 150 miles per second. You wouldn’t even notice it. At best, you might spot the briefest flash of light. You would never know it was a car.

Credit: NASA

The human visual experience always depends on speed, size, and distance. The International Space Station (ISS) races along at almost 5 miles per second, or 17,500 miles per hour. At that speed, it orbits the Earth in 90 minutes. The astronauts are moving so fast they see a sunrise and sunset every 45 minutes. The ISS is as big as a football field, but it is 200 miles away from the surface of the Earth. So, when we gaze into the night sky, ISS looks like a bright, slow-moving star.

New Telescope

Since 1968, we have launched more than 90 space telescopes into orbit—most from NASA and ESA, the European Space Agency. The next telescope to rise above our murky atmosphere will be SPHEREx. Yes, its name is another NASA acronym: SPHEREx stands for Spectro-Photometer for the History of the universe, Epoch of Reionization and Ices Explorer.

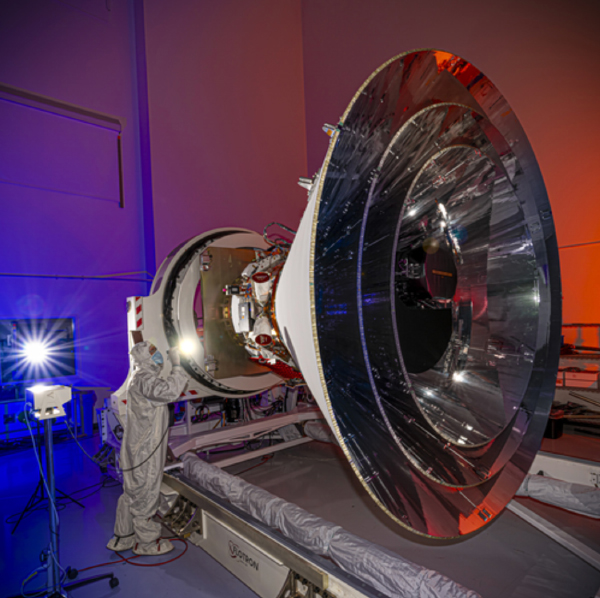

Due to launch this month, this space observatory will survey the galaxies in our sky in optical and near-infrared light. Its goal is to better understand our early universe—how the first stars and galaxies formed—as well as search for water and organic molecules in distant stellar nurseries.

SPHEREx animation; Credit: NASA, Caltech

The telescope is small, about the size of a sub-compact car, and has an interesting cone-like shape from its three photon shields, which will keep the telescope cool from the heat of the sun and Earth. SPHEREx's near-infrared capabilities will address a particular blind spot in our current fleet of space observatories.

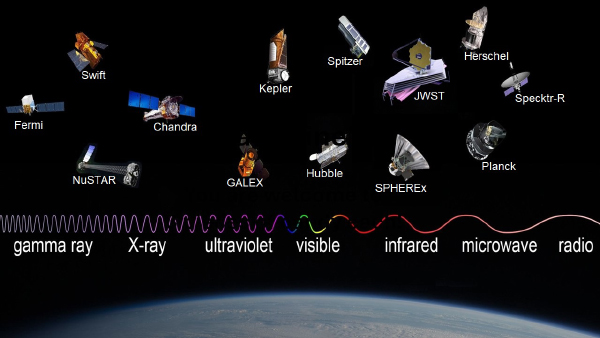

With all the space telescopes up there, it begs the question: Why do we need so many different observatories to look out at the universe?

For most of human history, when we look out into space with our eyes or a backyard telescope, we observe what we call visible light. Though beautiful and grand, this is an extremely narrow band within the vast electromagnetic (EM) spectrum. How narrow? This visible light is only 0.0035% of energy coming from the universe. That is a very tiny amount.

Sampling of Space Telescopes; Credit: NASA

To observe most of the EM spectrum, we need to get above the clouds. Only visible light and radio light reach the surface. So, we place telescopes in space to view light and energy from these key parts of the spectrum—gamma, x-ray, UV, infrared, and microwave.

A notable example of collecting energy and light from different wavelengths is this image of the Crab Nebula—remnants of gas and dust from a supernova in the constellation Taurus in 1054.

Crab Nebula in 5 Wavelengths; Credit: NASA HubbleSite

Seeing the Crab Nebula in 5 different forms of light and energy allows scientists to construct a more well-rounded understanding of supernovae and stellar evolution. The five different telescopes are:

- Radio: Very Large Array

- Infrared: Spitzer Space Telescope

- Hubble: Optical or Visible

- Ultraviolet: XMM-Newton

- X-Ray: Chandra X-ray Observatory

SPHEREx will be the first mission to observe in the near-infrared—a part of the EM spectrum that our current space observatories do not observe. Each category of the EM spectrum has many sub-groupings. SPHEREx’s goal is to make an all-sky spectroscopic survey, which will take space images of the entire celestial sphere, producing a comprehensive map of everything in the near-infrared.

SPHEREx plans to conduct the first all-sky spectroscopic surveys every six months in 102 infrared colors. This type of light is ideal for studying stars and galaxies at varying points in cosmic history. This is particularly important for understanding cosmic inflation, the nearly instantaneous event of rapid cosmic expansion that took place in the first billionth of a trillionth of a trillionth of a second after the Big Bang.

By looking at the total glow of over time, scientists will get a big-picture perspective of the universe, and after charting the 3D locations of hundreds of millions of galaxies, the influence of inflation on the large-scale structure of the universe today will become more apparent.

SPHEREx being tested; Credit: NASA, Caltech

SPHEREx adds a missing piece of EM spectrum puzzle. All the telescopes in space have their specializations, forming a web of coverage for further scientific inquiry. Our unaided eyes only give us one perspective, so by having an entire fleet of advanced technologies, we can better uncover the secrets of our universe!

Einstein’s Ring

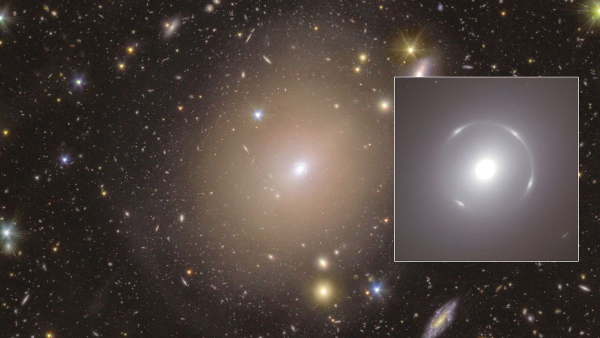

What is special about an Einstein Ring? Well, it has nothing to do with a marriage proposal, but it is an awesome and out-of-this-world ring nonetheless!

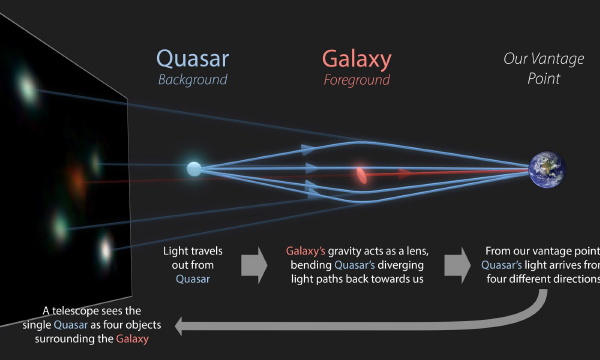

An Einstein Ring is a fascinating trick of light on cosmic scales. They are the product of a phenomenon called gravitational lensing, the warping of spacetime that was discovered by Albert Einstein. He predicted this in 1915 with his theory of general relativity.

Credit: NASA; Rock Collection by Perseverance Rover

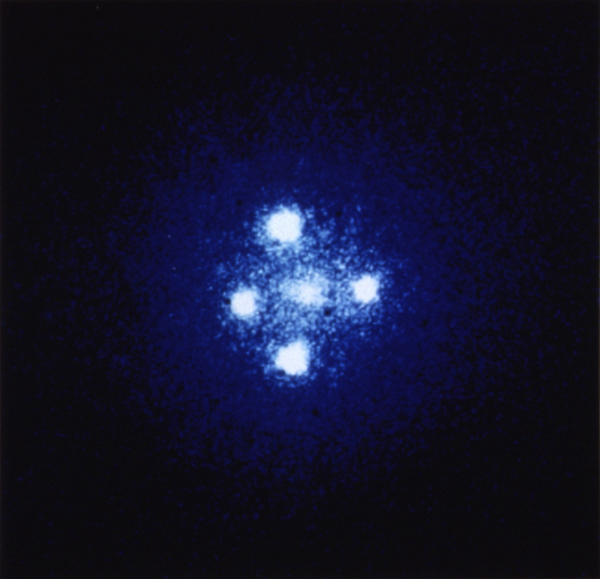

An Einstein Ring happens when a distant galaxy emits light in all directions, but it is all bent back towards us here on Earth by a massive foreground galaxy. When the light reaches us, the image of the faraway galaxy has been warped and duplicated so that it forms a ring around the image of the foreground galaxy. Something similar happens with a distant and bright point source, like a quasar. A quasar is a galaxy with a supermassive black hole at its center that emits copious amounts of energy. Quasars are the most luminous objects in the universe and are a type of Active Galactic Nucleus (AGN). When the quasar’s light gets bent by the gravity well from the foreground galaxy, we do not see a ring—but an Einstein cross. It looks like four dots circling a bright central object.

Credit: R. Hurt (IPAC/Caltech)/The GraL Collaboration

Einstein Cross; Credit: NASA, ESA, and STScI

When Einstein was a young boy, he was enraptured by physics and mathematics. He was mystified by the unseen forces that moved the needle of a compass and considered his first geometry book a sacred possession. At 16 years old, he began pondering the question of “what would it look like if you ran alongside a lightbeam?” And thus began his development of the theory of relativity.

While we may think of Albert Einstein as a revolutionary genius now, he initially struggled to find his footing in physics. During his school years, he had done poorly in his courses not related to math or physics, and he skipped so many classes that his professors wouldn’t recommend him for academic positions. He had trouble keeping a job, even as a children’s tutor.

Credit: T. Pyle/Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab

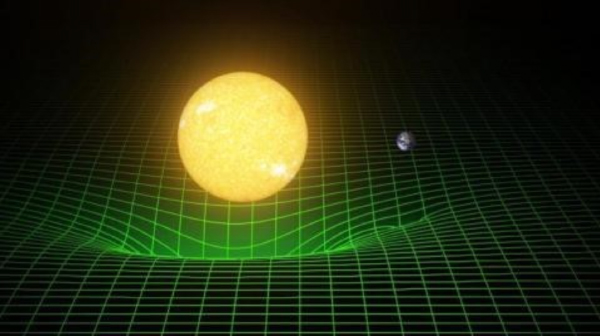

Einstein theorized that space and time are woven together into a four-dimensional fabric called spacetime. The way you move through space impacts the way you experience time. This fabric can be bent by mass, like how a trampoline will droop a bit if you sit in the middle. In turn, other masses will orbit and fall according to the curvature of spacetime. If someone placed a marble at the edge of the trampoline and let go, it would roll right towards you. If they gave it a push along the rim of the trampoline, the ball would spiral in, like an object in orbit. Einstein said, “Matter tells spacetime how to curve, and curved spacetime tells matter how to move.”

It isn’t just objects with mass that are impacted by gravity’s pull! The otherwise-straight path of a photon will curve if placed in a gravitational field. This means that very massive objects like stars, black holes, and galaxies can bend light and alter our cosmic observations. That’s gravitational lensing!

Credit: NASA, ESA, and STScI

When the light from a faraway object in space gets lensed by something between us, it can create some wild images, like this galactic smiley face.

Space in Sixty Seconds

All seven planets in the sky at one time? A Pi Day Lunar Eclipse? Find out more…

Sky Sights

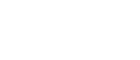

The Moon, Venus, and Mercury form a beautiful celestial trio March 1 and 2. Mercury will be visible until around March 10 as it fades in brightness and altitude above the horizon. Venus is sinking, too, visible until about March 15. On March 22, Venus is at inferior conjunction, meaning it will pass between the Earth and the sun and thus will not be visible. It will quickly return to the morning sky in early April.

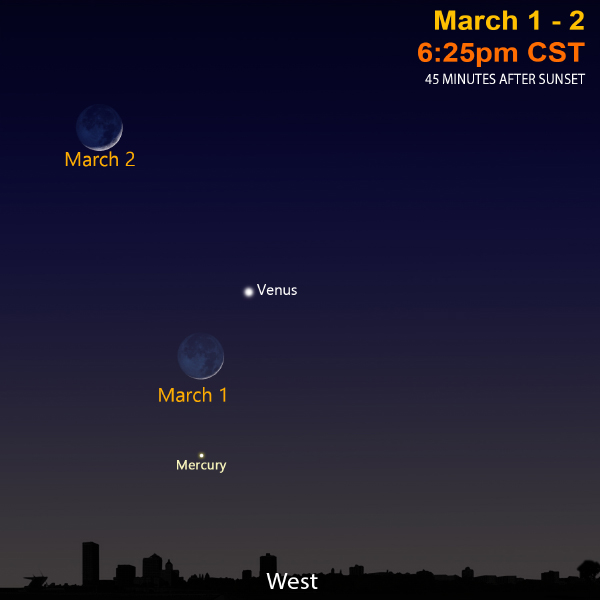

Jupiter still reigns high in the south sky after sunset. Look for it above the stars of Orion the hunter and very near the bright star Aldebaran. The Moon orbits by on March 5 and 6.

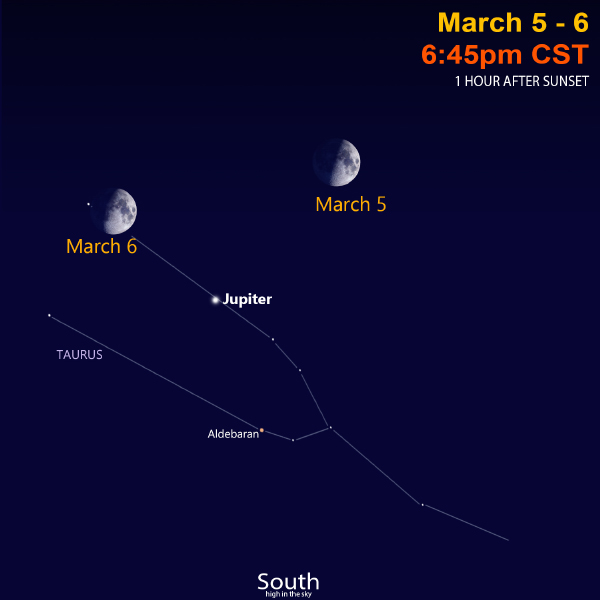

On the next two nights, March 7 and 8, the Moon meets up with the red planet Mars and the two bright stars in Gemini, Castor and Pollux.

On the night of Thursday, March 13 and 14, there will be a total lunar eclipse—the first one since 2022. The eclipse times are frightful—starting after midnight and going to almost 4 a.m. CDT.

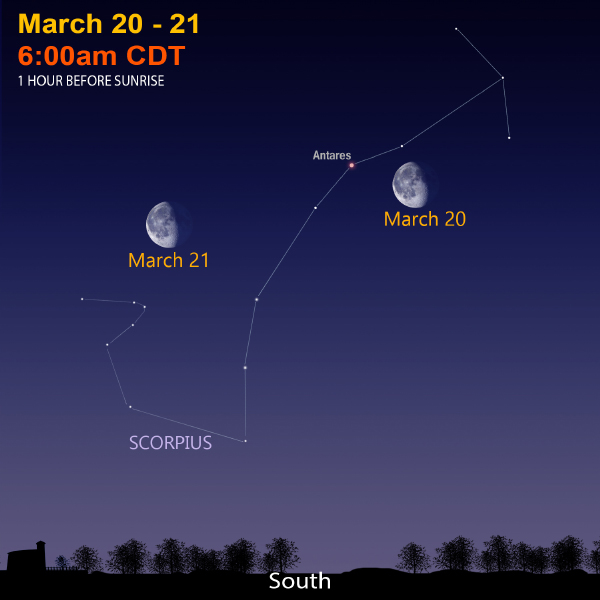

On the first night of spring, March 20, early risers can catch the waning gibbous Moon shining near the red star Antares in Scorpius.

March Star Map

Sign Up

Receive this newsletter via email!

Subscribe

See the Universe through a telescope

Join one of the Milwaukee-area astronomy clubs and spot craters on the Moon, the rings of Saturn, the moons of Jupiter, and much more.

Follow Bob on social media

Twitter: @MPMPlanetarium

Facebook: Daniel M. Soref Planetarium