The 12 samplers of the ABCs of Schoolgirl Samplers exhibition are drawn from more than 40 examples within the Milwaukee Public Museum’s extensive textile and clothing collection. They are representative of school-related samplers during a narrow 66 year period of time, 1790-1856, and include examples from the United States, England, Germany, and Mexico. While such a small sampling cannot depict the full variety of sampler-making during this period, it is an adequate representation of schoolgirl samplers from the Museum’s collection that reflects cultural and social variation, and was stable enough for exhibition. It is hoped that the 12 examples chosen for exhibition have enough diversity to please an interested audience with their range of patterns, needle skills, and design abilities of their young makers.

Architectural Samplers

Fig. 1 — The Mary B. Hammond sampler has all the graphic appeal that sampler collectors covet. Besides the obligatory alphabets and numerals, Mary chose to charmingly depict the two-story village inn squarely in the center of her sampler to reflect the importance of the public house to the economy and permanent establishment of her early New England community. She identified the building with a simple sign with the word “Inn” hanging high from its roof, and also included garden structures, a gate with a birdhouse perched on top, a wide variety of trees -- several which look to be fruit trees -- clouds in the sky, and a sweet little kitty. Her charming sampler reveals a young girl’s burgeoning needle skills and ability to design her own unique work by artfully filling its surface with architecture, foliage, sky, and objects of both sweet sentimentality and real importance to her unnamed village.

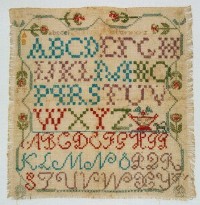

Marking Samplers

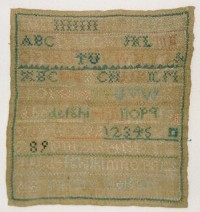

Fig. 2 — In contrast to Mary Hammond’s effort is Anna Hemenway’s simple marking sampler, done all in cross stitch with humble linen floss on a plain linen ground. Anna completed three different alphabets and her full date of birth, “born March 27, 1784,” but did not finish the rest of the piece. We do not know Anna’s exact age, but since the sampler is simply designed, it may have been her first needlework attempt. Since she was young, perhaps six years or so, the sampler is estimated to be worked around 1790. Done in traditional band style, the sampler was possibly done in an informal learning situation like a neighborhood school by a teacher who taught plain rather than fancy needlework. Unfinished samplers are not uncommon, but in speculating why Anna may not have completed her sampler, we must consider the obvious reasons like illness or death; but she may simply have had little motivation to finish because of lack of interest or poor aptitude.

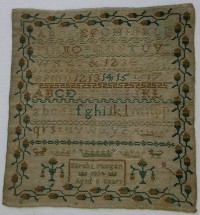

Fig. 3 — The sampler stitched by Fanny Reigart is also a simple marking sampler, but it has a vertical rather than horizontal orientation, and its surface is filled with a variety of alphabets, numerals, decorative dividing lines, and a decorative border on all four sides. While the orientation is typical of the top-to-bottom and left-to-right sampler design of England and the United States, Fanny enriched its graphic appeal by using a wide color palette of silk flosses in eight shades of blue, red, green, yellow, brown, and black. Her liberal use of silk, a higher quality material than linen floss, may indicate that Fanny had a considerably higher degree of proficiency than Anna Hemenway, was taught by a more accomplished teacher, and/or made the sampler at an established school that taught more affluent girls and that could offer higher quality materials and instruction to their students.

Biblical and Moral Verses

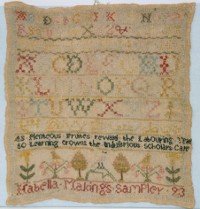

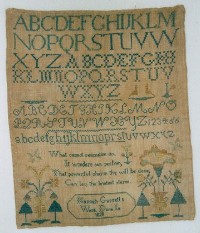

Figs. 4 and 5 — Along with alphabets and numerals, schoolgirls might also include a line of poetry or a passage from the Bible on their sampler. Stitching a verse onto one’s sampler not only augmented the memory but was thought to reflect the piety of the maker. Two examples from the exhibition are the Isabella Makings sampler from 1793, and Hannah Garret’s sampler from 1820. Both verses are instructions in proper decorum and the benefits of hard work. Isabella’s is believed to be English and includes seven different royal crowns indicating different levels of English aristocratic rank. In comparison, Hannah Garret’s sampler with verse is believed to be American, based on the opinion of a New England antique dealer who sold the piece to the Museum in 1912. It came with no accompanying provenance.

German Samplers

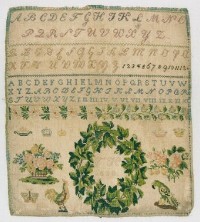

Fig. 6 — The sampler exhibition at the Milwaukee Public Museum would not be complete without representation of Milwaukee’s largest immigrant group in the nineteenth century –- Germans -- and includes three very different examples. T.K.’s sampler (fig. 6) has several telling elements of its German origin, one of which is alphabets in both Latin and old German gothic script. It contains motifs frequently found on German made samplers: a large leafy wreath, parrot, and a rooster, all of which are executed in tent stitch. It also contains crown motifs to denote German aristocratic rank.

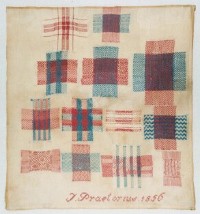

Fig. 7 — Another German-made piece is T. Praetorius’s sampler. Hers is referred to as a darning sampler and displays 13 spot motifs of various mending techniques (fig. 7). Darning samplers differ from schoolgirl embroidery band samplers in both technique and design. While schoolgirls learned embroidery stitches for embellishment and marking of household textiles, textile repair was also a necessary chore and many girls created samplers to practice that skill. Some darning samplers include decorative floral embroidery motifs which add to their charm, while others contain only darning samples placed on a linen ground fabric in rows or spots displaying mending examples for a variety of different fabrics and weaves. These mending techniques could later be used by the needlewoman to fill in a moth hole or to repair a tear, making a damaged piece of clothing serviceable once again. The darning sampler in this exhibition was made in 1856, a late date for a schoolgirl sampler. It still retains all of its vivid blue and red color which may indicate that this sampler was not made for display, but stored away and brought out only when a reference for a repair was needed.

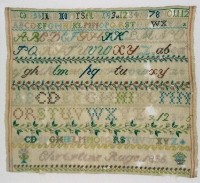

Fig. 8 — The third German sampler in the exhibition is a lively, colorful marking sampler made on wool by a German immigrant to Milwaukee, Christine Ruge in 1836 (fig. 8). The Museum has in its collection four samplers from this maker. Done in Germany before she came to America, Christine used silk floss to completely fill the fabric surface with five alphabets, highly decorative floral dividing lines, and her name prominently executed in large cursive letters. The intense colors of the flosses that Christine had access to and used in her sampler may reflect Germany’s dominance in manufacturing superior, stable textile dyes in the nineteenth century. Despite its fragile condition due to insect damage to the wool, the sampler has retained all of its colorful charm and design.

Fig. 9 — Another colorful sampler in the exhibition is a dramatic contrast to the other samplers and appears not to have been made in continental Europe or the United States. A gift to the collection in 1916, it was originally attributed to a German maker, but now is believed to be of Mexican origin because of its overall appearance, execution, stitch selection, and the most striking difference between it and the pieces from Europe or the United States is its orientation.

The sampler reflects Spanish characteristics by its oblong shape and the absence of alphabets or numerals. It also is in the Spanish style as different embroidery stitches are grouped into vertical and horizontal bands that are positioned above, to the sides, and below the center where the maker, “D.M.,” included her initials and date of 1804. Varieties of satin stitch dominate this sampler as in many Spanish samplers, but the sampler indicates a Mexican origin as the maker included a variety of stitched patterns in pulled thread, Assisi work, tent stitch, cross stitch, and Algerian eye. Also in the Mexican style, the maker included some floral motifs unlike European examples. Unlike European and American examples, the linen ground is finely woven and the stitching executed in such a way that the back is as beautiful as the front -- very characteristic of Mexican needlework.

Fig. 10 — The use of vibrant colorful flosses used in this sampler indicates the use of synthetic dyes and therefore a later date of completion, probably mid-nineteenth century. Believed to be made in the United States by an unknown maker, the sampler is curious because the vine floral border is executed in silk floss, while the three alphabets, vase with flowers, and dog are inexpertly fitted within the border in wool floss. Perhaps the border was completed first, and the alphabets and motifs at a later date. Outside of the vine border close to the edge are two sets of twin letters, “A B” and “F T.” They may indicate a partial alphabet begun and placed to fill in an empty space, or more likely they are the maker’s initials and perhaps one other individual. The sampler is also the only example in the exhibition with a fringed hem, another indicator of its mid nineteenth date.

All 12 of the samplers in the exhibition display a variety of finishing treatments to its edges. Techniques such as hemming, as well as embroidery and mending, were necessary needle stills. Samplers could be hemmed on two, three, or four sides, and frequently their makers utilized the selvedges to finish an edge as either a frugal use of cloth or to eliminate the need to hem all four sides.

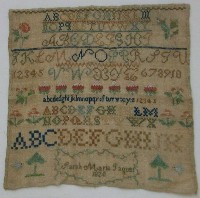

Figs. 11 and 12 — The last two samplers under discussion demonstrate the frequent use of the strawberry motif in both English and American-made samplers. In the American example dated 1820, Sarah Marie Jacques stitched seven plump strawberries in cross stitch as a large decorative dividing line between alphabets. She used two shades of pink in each naturalistic berry, and gave each a green stem. Sarah L. Morgan used the strawberry motif in a continuous line creating a delightful strawberry border design which frames her sampler. More geometric in feel than Sarah Jacques’ strawberries, her choice of floss is also less naturalistic, and now has changed to a gold tone and could be taken as a line of acorns rather than strawberries. While most samplers from the late-eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth century used silk, linen, and later wool flosses, Sarah Marie’s example is most insightful for she used a cotton-linen blended floss for her letters, and silk floss for all of the floral motifs. Cotton floss at this time is unusual and gives evidence to the beginning use and availability of cotton floss in decorative embroidery.

The 12 samplers from the ABCs of Schoolgirl Samplers exhibition reflect the typical rather than the unusual, providing a window into sampler design and purpose. The examples were selected for their diversity to provide an overall view of the decorative and functional embroidery performed by young girls, but limited by necessity in its focus because it does not include examples of schoolgirl embroidery from African-American girls, nor examples of sampler-making from the southern United States or Eastern Europe.