The beings that make up Kwakiutl mythology are remarkably diverse. Accounts of their interactions with humans and each other are passed along through stories that not only form the basis of traditional Kwakiutl spiritual and ceremonial life and lore, but also connect Kwakiutl families to their ancestral pasts. Many contemporary Kwakiutl identify themselves as Christians but incorporate traditional mythology into their faith, freely blending elements of Christian and indigenous religion. Broadly speaking, Kwakiutl mythology divides the world into several realms: the mortal world, the sky world, the land beneath the sea, and the ghost world (Boas 1935: 125; 1966: 306; Hawthorn 1967: 19; Macnair 1998: 95). In reality, however, it is difficult to discuss Kwakiutl mythology uniformly owing to the diverse accounts found among the many bands that constitute the Kwakiutl First Nations, though some underlying commonalities exist (Joseph 1998: 18-19, Kwakiutl Indian Band 2009; U’mista Cultural Center 2009).

Kwakiutl creation stories exhibit tremendous variation, but all hold that the original people appeared a very long time ago and presume the Earth to have already been in existence at that time (Bancroft-Hunt and Forman 1979:89-90). Some creation myths, known as transformation stories, tell of ancient ancestors traveling the world transforming nature or themselves into new beings, some taking off their animal masks to reveal their human selves. These ancestors imparted their animal masks as crests for their numaym (lineages), thus identifying some numaym with specific animals, such as the killer whale, wolf, bear, or raven. Some of these characters use their ability to transform to play tricks or to escape the consequences of their actions. Still other tales recount ancient ancestors’ encounters with supernatural visitors, angry spirits, and elemental forces. The list that follows includes brief descriptions of some of the more notable characters in traditional Kwakiutl cosmologies that are represented in the Barrett collection.

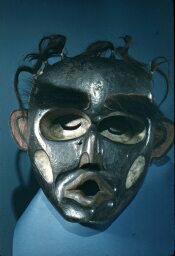

Buk’wus (Wild Man of the Woods): This character is one of the most fearsome in Kwakiutl mythology, even though it is generally reclusive and shy of people. The spirit of Buk’wus, Chief of the Ghosts and woodsmen, is said to live in the forest in a house that is invisible by day, subsisting on ghost food and cockles and drawing the spirit of the drowned to his side. He sometimes entices people to feast with him on his ghost food, thus eternally trapping them in the spirit world and eventually turning them into a Buk’wus (Mochon 1966: 72; Hawthorn 1967: 291; U’mista Cultural Center 2009).

Crooked-Beak of Heaven: These supernatural birds, easily identified by their dramatically arched beaks symbolizing hunger, are the attendants of the chief cannibal spirit and their duty is to provide the spirit with bodies to devour. They are believed to travel down to the eartth when they are hungry, seeking people to devour, and also play an important role in completing the secret Hamatsa ceremony (For more on the Hamatsa society, see the section entitled “Kwakiutl Ceremonial Life”).

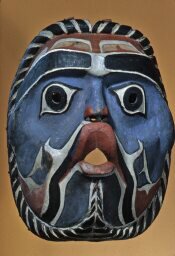

Dzunukwa (Wild Woman of the Woods): There are many tales about Dzunukwa, though all describe her as a towering, clumsy, wide-mouthed, hairy woman with deep-set eyes and an appetite for disobedient children. She lives with her babies in a house guarded by Sisiutl (see Sisiutl below) set deep in the woods, where she hoards treasure and spends much of her time sleeping. Though terrifying, Dzunukwa can also be moved to generosity and kindness and will even give great treasure to anyone who can make her babies cry. Unlike many Kwakiutl deities that are thought to have fled from the physical world, retreating from the machinations of modern society, Dzunukwa is believed to still physically inhabit the dense mountainous forests of the Pacific Northwest (Holm 1972: 33; Cole 1991: 138; Jacknis 1991: 198, 206). For many people, Dzunukwa is probably better known by her Chinook name, Sasquatch, or her English name, Big Foot.

Kumugwe (Copper-Maker, or Wealthy One): God of the land beneath the sea, Kumugwe is associated with tremendous wealth and lives with his wife in an undersea palace made of copper planks guarded by an assortment of sea creatures. It is said that the posts of his house are living sea lions and its doors are like giant, snapping mouths, and that within the walls of his palace is hidden great treasure. If a mortal could reach the sea god’s palace alive they would return home as wealthy and powerful men, for Kumugwe can bestow not only wealth but also magical powers (Boas 1935: 128-130; Hawthorn 1967: 239-240; Macnair 1998: 129). He is also regarded as the adversary of the Thunderbird.

Nu?ama?a (Fool Dancer): These characters are associated with the Hamatsa and are responsible for enforcing the laws that govern proper behavior during the ceremony (For more on the Hamatsa society, see the section entitled “Kwakiutl Ceremonial Life”). Nu?ama?a noses are extremely large and runny, and the mucus they secrete is considered magical and dangerous. However, the Nu?ama?a are very sensitive about their noses, and any mention of it or their mucus will only cause them to become agitated.

Raven: The Raven is considered to be a trickster according to Kwakiutl mythology, but his mischievousness has benefited mankind by providing us with the sun, moon, stars, fire, and salmon. He is also believed to be able to transform himself into any shape or creature at will.

Sisiutl: A two headed sea serpent with a humanoid face in the center of its body, the Sisiutl is not only easy to recognize but is also one of the most powerful and important beings in Kwakiutl cosmology. It is believed that anyone who sees a Sisiutl will be turned to stone, and walking in the trail of slime that Sisiutl leaves in its wake entails certain doom. Having impervious skin that cannot be pierced, Sisiutl is the assistant of the war spirit Winalagilis, and it is believed that any warrior who can harness Sisiutl will be blessed with great powers. However, the Sisiutl can be killed by striking it with weapons covered with the blood from one’s tongue. This supernatural creature can transform itself into a number of other creatures, and can change its size at will. Those privileged to wear the Sisiutl as their crest are held in very high esteem, as they are afforded the protection and benevolence of the creature. The Sisiutl, along with the Thunderbird and Dzunukwa, are the three most important lineage crests representing supernatural entities (Boas 1935: 146; Hawthorn 1967: 133; Jonaitis 1991: 61, 90).

Thunderbird: These mythical horned birds inhabit the highest reaches of the sky, and are rumored to cause thunder when they ruffle their feathers and lightning when they blink their eyes. Thunderbirds are often transformers, changing from birds to humans (often recognized as ancient ancestors), and are associated with specific communities and lineages. Thunderbirds are generally protective spirits, as are their close relatives the Kulus (Holm 1972: 47; Suttles 1991: 90; Macnair 1998: 100; U’mista Cultural Center 2009).

Kwakiutl Ceremonial Life

As with Kwakiutl art and cosmology, Kwakiutl ceremonial life is complex and varies somewhat according to local traditions and familial events. The year is generally divided into two ceremonial periods, summer and winter, which consist of dance cycles that culminate in a potlatch. The Potlatch is the center of traditional indigenous life throughout the Northwest Coast, and can be understood as an event whereby a noble family invites guests to celebrate a particular event and witness a display of the host lineage’s wealth and status (Kirk 1986: 30; Jonaitis 1991: 11). These events can range from the transfer of marriage privileges and naming ceremonies for children, to the acquisition of new rank and the initiation of a dancer into a dancing society (Hawthorn 1967: 25). During a potlatch, the head of a lineage will distribute an array of gifts (such as blankets, copper pieces, cedar bark, money, even cars and canoes) to friends, family, and neighboring clans in a display of wealth that creates bonds of social obligations between the attendants and the wealthy chief. The Potlatch creates significant tensions owing to the indebtedness of attendants to the chief, who will expect some form of future repayment (in the form of money, labor, political favors, etc.) for his generosity. This repayment is often at tremendous rates of interest that might take years to repay or that vastly outweigh the value of the initial gift.

The origins of the Potlatch are difficult to trace, especially owing to the intensive interaction of Kwakiutl and other First Nations prior to colonial contact. Yet, it was likely the threat of colonial conflict that encouraged Kwakiutl communities to create new alliances with other Kwakiutl communities, prompting the expansion of potlatching and joint winter season ceremonies (Suttles 1991: 113). The Potlatch has a long and complex cultural and political history, and has undergone some significant changes as a consequence of European colonization and the rise of capitalism (Ringel 1979; Kirk 1986: 62-63; Webster 1991: 227). Often misunderstood, the Potlatch has captured the imagination of anthropologists for some time, and it has even been suggested that a history of anthropological thought could even be written simply by examining the ways anthropologists have interpreted the Potlatch over time (Masco 1995: 41).

At one time, the ceremony was considered a threat to colonial rule, so much so that the Potlatch was banned in Canada from 1884 until the 1950s. It was condemned by colonial authorities as an act of economic destruction and civil disobedience, and for its alleged “savagery” owing to the ceremonial incorporation of non-Christian deities, folklore, and performances of mock-cannibalism and spirit possession. Several Kwakiutl families and communities deliberately broke anti-potlatching laws, laws that were often punishable by severe fines or imprisonment. It was within this climate of ceremonial prohibition that many masks and regalia were confiscated by police and either destroyed, warehoused, or sold to museums. Since the lifting of the ban, First Nations have tried with some success to reclaim masks, ceremonial raiment, and other regalia associated with the Potlatch. However, these reclamation efforts have mostly been on the terms of the Canadian and American governments, and have generated tensions that largely remain unresolved (Jacknis 1996: 284). Nevertheless, since the lifting of the ban many Kwakiutl communities have experienced something of a cultural renaissance, with many bands creating their own museums for their returned regalia, developing carving programs for band members, and inviting tourists to visit their reserves to learn about Kwakiutl heritage and history (Joseph 1991: 16, Mauzé 2003; U’mista Cultural Center 2009).

It is generally held that there are two basic contemporary Kwakiutl Potlatch ceremonies, each varying in size and scale and involving ritual dances: the T’seka, or Winter Ceremonial dance, and the less prestigious T?a’sa?a dance. Whereas in the past, the two types of dances were never performed together, today it is common for the dances to be performed on the same day, in the same house, and even by the same people (Jonaitis 1991: 12). The dances, songs, regalia, and accompanying masks associated with each type of ceremony are performed by particular lineages who own the sole right to these performances. The question of ownership of these ceremonial performances and objects is sometimes the cause of great stress and controversy among contemporary Northwest Coast Indian communities (Kirk 1986: 38; Kramer 2006).

The T’seka ceremonial sequence is celebrated in winter, a season that the Kwakiutl associated with supernatural beings and events, and usually begins in November. The winter season is also the perfect time for grand indoor ceremonies, as people try to avoid the cold rains of winter and enjoy the fruits of their summer and fall labors, such as smoked fish and fish oils, dried meats, berries, fruits, and nuts. The organization of a band during the Winter Ceremonial is based on the function of various groups according to their role as managers (shamans), performers (usually close relatives), and initiates, with the uninitiated taking no active role in the ceremonies (Boas 1966: 173-174). Managers bestow upon initiates the privilege of performing certain dances and masks, which are said to come from an ancient ancestor who bestowed these gifts as sacred privileges. The performance of these bestowals during the ceremony serves as an initiation of the novice into their numaym’s (lineage’s) dance society. During ceremonies, the rank of these dance societies outweighs normal social ranking, so much so that during these events people may only address one another by ceremonial names or risk suffering severe penalties (Bancroft and Forman 1979: 110).

The Winter ceremonials summon the fearsome and powerful beings of the spirit world, including the most powerful and dreaded of all the supernatural beings, the Cannibal Spirit. This spirit possesses initiates of the most highly ranked of the Kwakiutl secret dance societies, the Hamatsa (cannibal society), and can only be forced to leave the body of the initiate with the guidance and intervention of shamans and close relatives. These performers, adorned with eagle down, red cedar bark (representing human flesh) and black paint, give embodiment to a wide array of animated spirits like cannibal birds (servants of the Cannibal Spirit, such as Raven, Crane, Crow and Crooked Beak), Nu?ama?a (Fool Dancers), and others.

The T?a’sa?a Ceremonial, which invokes the appearance of animal spirits and ancestors, is smaller and perhaps less intense than the T’seka, and considered to be a secular event owing to the absence of shamanic rituals common to the Winter Ceremonial and the presence of familial crests. In T?a’sa?a (Chief’s Dance) ceremonies, performers are typically dressed in cormorant down, white cedar bark, and red paint, and focus on the performance of folktales or mythical origin or transformation stories of their particular lineage (Jonaitis 1991: 28, 42; Stolte 2009: 21). Sometimes, the characters represented and embodied by animal or ancestor masks do not dance alone but interact with one another as a team. In addition to masks of animals and ancestors, it is not unusual for human-like creatures such as Buk’wus, Dzunukwa, Kumugwe, and others to make an appearance (Suttles 1991: 114).