Robert Ritzenthaler and Frederick Peterson: An “Ethnographer’s Paradise” (1954)

As part of his duty as curator of anthropology, Robert Ritzenthaler obtained cultural artifacts for the collections at the Milwaukee Public Museum. Whether in Palau, Cameroon, or Illinois, each excursion yielded potential research materials and subject matter for scholars everywhere. During a trip to the Museo Nacional in Mexico City to examine artifacts, he came across items that looked very much like Woodland Native American items. When Ritzenthaler asked about the pieces, he was told that there was a group of Kickapoo that had been living in the state of Coahuila since the 1850s. Shortly thereafter, he decided to organize a trip to observe the Mexican Kickapoo. This was not the first study conducted on the Mexican Kickapoo (Fabila 1945; Goggin 1951); however this trip was intended to be the longest exploration of the group since their arrival in Mexico.

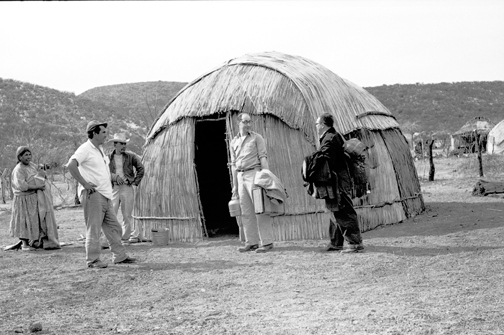

“Ritzenthaler and Peterson in Front of a Shelter”

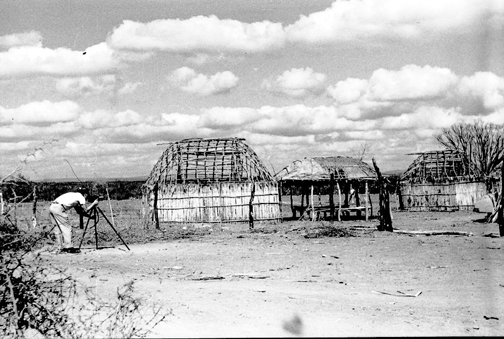

“Filming”

In 1953, Ritzenthaler secured Frederick Peterson as his primary research colleague and photographer. Peterson lived in Mexico City and was frequently involved with various projects in Mexico, an advantage for dealing with Mexican national authorities as he was fluent in Spanish. After much planning, including obtaining permission from the civil chief in the area to conduct their study, Ritzenthaler and Peterson arrived in Muzquiz, the town closest to the Kickapoo village, in January 1954. Before going into the village, they acquired a native Kickapoo guide and a nearly fluent Spanish speaker that would be willing to assist them with their intended 4 month ethnographic study.

Arriving in the village, they encountered what they described as an “ethnographer’s paradise” (Ritzenthaler and Peterson 1956:9). Despite the long journey from the Great Lakes region begun some 300 years earlier, the Mexican Kickapoo retained many of the hallmarks of Woodland material culture. The tribe continued to live in the traditional reed-covered wigwams, rotating from summer to winter homes just as they had in and around in the northern Midwest area of the United States.

“The Researchers Arrive”

“Photographing a Kickapoo Woman”

During the first week and a half of their stay in the village, Ritzenthaler and Peterson were met with mixed reactions from the male participants in the village. On day ten, Ritzenthaler and Peterson were called before the council, 34 men in total, and were told to leave the village. Though they had secured permission from the civil chief who was recognized as such by the Mexican Government, he was not considered the highest authority amongst the Kickapoo tribesmen. Another reason for the council’s decision had to do with their New Year ceremonies, which were to begin in several weeks. No foreigners – Americans, Mexicans or otherwise – were allowed to attend, participate, or view the events, and the religious chief had advocated for their immediate expulsion from the village to prepare for the events. Ritzenthaler and Peterson asked for 4 days to finish up their collection of ethnographic artifacts and were granted this grace period. The two men spent an additional week in Muzquiz meeting with informants and collecting additional information on the group. Despite this abbreviated field season, the two men managed to record copious field notes, take almost 100 black-and-white photographs and 1100 feet of color motion picture film, collect artifacts and conduct interviews with several participants. Ritzenthaler considered petitioning the council members to return after the New Year’s celebration “but decided that it would be in the best interests of future field workers not to chance a possible altercation” (Ritzenthaler and Peterson 1956:9).

Felipe and Dolores Latorre: In Admiration of “A Remarkable People” (1960-72)

Using the Ritzenthaler/Peterson expedition as a cautionary tale, Felipe and Dolores Latorre took their time in establishing a rapport with the tribe before attempting to study the group. What resulted from their patience was a twelve year friendship with the Mexican Kickapoo and the most comprehensive study of the group yet written. With the exception of the Ritzenthaler/Peterson study, most of the other publications failed to describe the cultural group ethnographically. All were able to describe the history of the group beginning in the Great Lakes down to Mexico, but once settled, the overall group dynamic within the Mexican Kickapoo tribe was not covered in the texts.

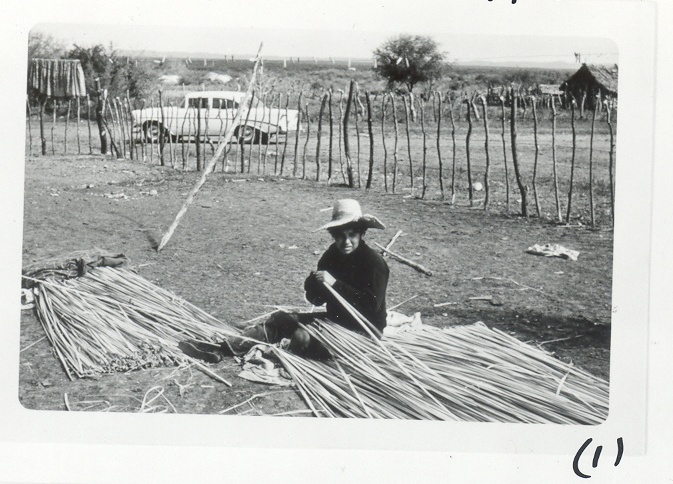

“Mat Weaving”

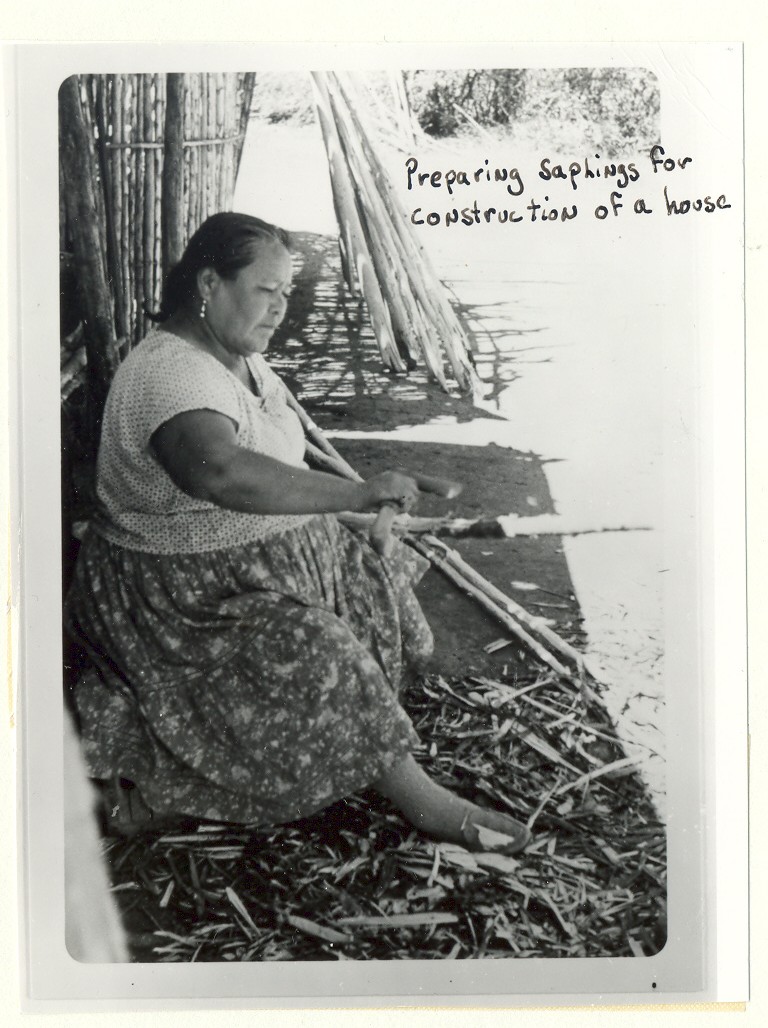

“Preparing Saplings for Construction of a House”

The Latorres carefully set about their fieldwork within the Mexican Kickapoo village, keeping in mind the trials of the Ritzenthaler/Peterson trip. A preliminary visit to Chief Papicoano, armed with a letter of introduction from former president Lazaro Cardenas, an advocate of the tribe during his term, only slightly influenced their cause. They rented a house in Muzquiz and mentally prepared themselves for a long wait. Over six months, the Latorres slowly gained the trust of the Kickapoo people that traveled into the town. Their efforts were aided by the fact that they were both native Spanish speakers. At the onset of their study, the Latorres were sometimes used for leverage in political disputes, or individual social gain, and they met with hostility within the community just as previous researchers before them (Latorre 1976). However, this tide of hostility came and went, particularly when they explained that this study would benefit future generations of Native Americans. Once finally accepted into the village and constantly maintaining a posture of patience and humility, Felipe and Dolores Latorre were able to collect information for ten years. During that time, they were entrusted with privileged information about tribal practices that no one had ever collected. The Latorres published their findings in 1976, stating that they hoped they had “in part, unraveled the mystery of the Kickapoos” (Latorre 1976:xix).