Beginnings in the Great Lakes

Though scholars find language the most efficient way to classify American Indian groups, many tribes would fall under broad language groups. The Kickapoo, meaning “those who walk the earth” or “he who moves here and there,” are grouped with other tribes in the Algonquian linguistic lineage, and were situated in what A. M. Gibson refers to as the “Algonquian heartland” (1963:3). This area was bordered on the east and north by the Great Lakes, on the west by the Mississippi, and on the south by the Ohio River. Tribes living in this region also possessed common cultural traits – a quasi-sedentary lifestyle, similarities in their methods of raising war parties, and their hospitable nature towards visitors.

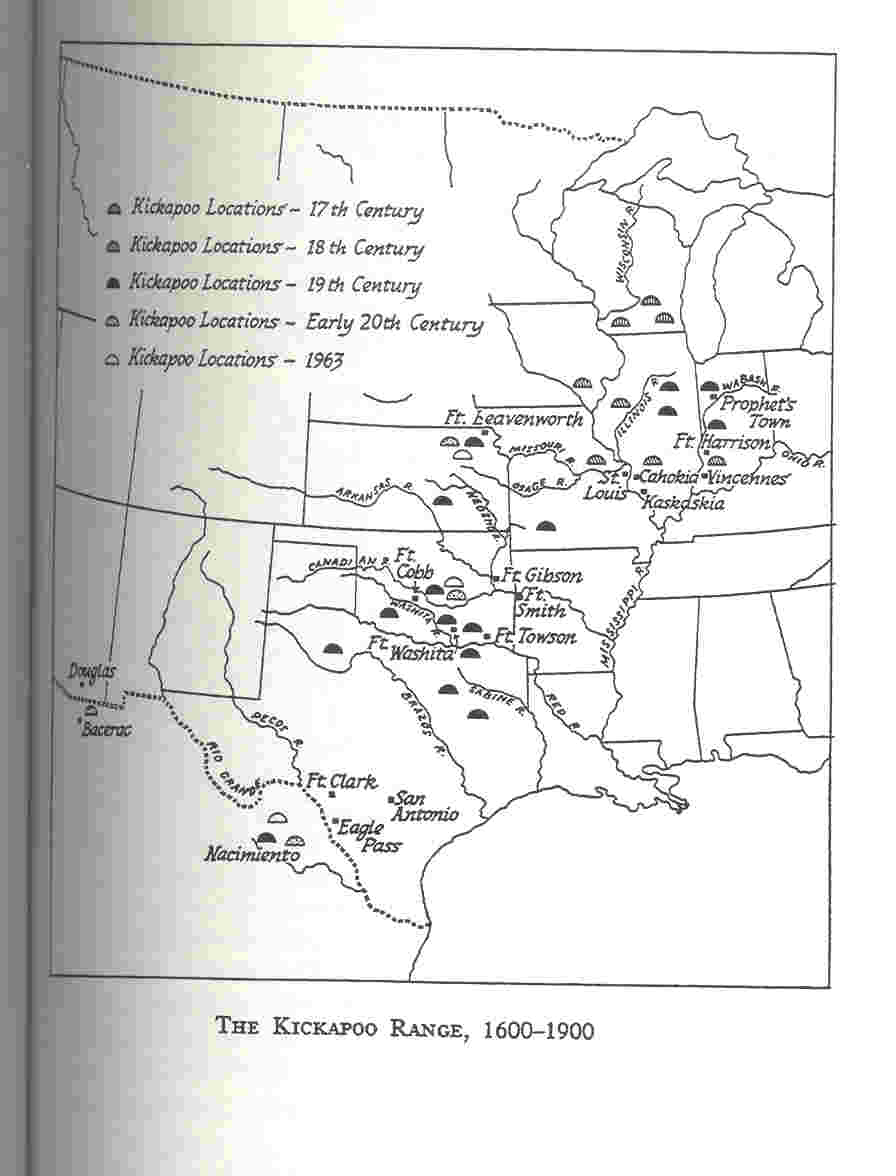

Kickapoo roots can be found in the Great Lakes region, and were first mentioned in Lower Michigan in the 1600s. By 1654, French explorers identified the Kickapoo, along with the Sauk, Fox and Potawatomi tribes, in southeast Wisconsin, having moved due to the heavy Iroquois influence in the east. Once the Kickapoo, in common with many American Indians, came into regular contact with Europeans, the actions of the tribe were guided by the will to survive - culturally, spiritually, physically and spatially. The Kickapoos maintained a love-hate relationship with the French, dictated by which tribes were allied against the French, the trade goods the French brought into the area, or the actions of settlers within particular areas. In 1765, the Kickapoo, Sauk, and Fox made their way into Illinois, where the Kickapoo set up camp near the city of Peoria.

This tenuous relationship, experienced first with the French, would be repeated with the English and the Americans. Settling in lands belonging to other native groups had always been a problem, but during the Revolutionary War the Kickapoo felt pressures begin to build exponentially. In 1779, the Kickapoo shifted allegiance from the British to the Americans under the promise of General George Rogers Clark, who stated that no American colonists would settle within Kickapoo territory (Latorre 1976:6). Unfortunately, several families from Kentucky followed the General into Illinois in hopes of settling land that appeared to be open and free, unaware of General Clark’s agreement with the native peoples in the area. Needless to say, Clark’s “broken promise” did not comfort the Kickapoo in any way and sent them to Detroit to seek the counsel of the British once again, in hopes of “stemming the American influx” (Latorre 1976:6). Skirmishes and in-fighting between allies and enemies alike occurred during the Revolutionary War. The Kickapoo again aided the British, providing their support to the foreign nation during the War of 1812. The tribe disliked the continual settling of sacred ancestral lands, and feared an American victory. After the defeat of the British, treaties were signed with the Americans dictating not only the terms on which the native tribes would be held accountable but the lands in which they were required to relocate their groups. Though the treaties temporarily brought peace and set aside land specifically for these tribes, the wave of American settlers slowly but surely infringed upon native space once again.

Migration

During President Monroe’s term (1817 to 1825) the overall policy was to force eastern Indian groups westward across the Mississippi River (Ritzenthaler and Peterson 1954). The Kickapoo signed a treaty with the U.S. government releasing 13 million acres of their land between the Illinois and Wabash rivers. In return, the Kickapoo would receive land in Missouri, near the Osage River, as well as a $2000 annuity for fifteen years. Of course this move placed the Kickapoo in close proximity with the Osage tribe, causing the two groups continuous conflict. During this larger western migration, the Kickapoo, numbering almost 3,000, split into several different bands and ranged from as far north as Lake Michigan to as far south as the Mexican territory.

“The Kickapoo Range (1600-1900)”

During the late 1820s, under the supervision of Cherokee Chief Bowles, a group of Cherokee, Delaware, Shawnee and 800 Kickapoo, were permitted by the Mexican government to relocate themselves from Arkansas to a spot outside of Nacogdoches, located in Eastern Texas. They established farms and villages, and were allowed to raise large herds of livestock. This somewhat peaceful existence was short-lived; the Mexican government offered a popular land-grant policy which attracted numerous American settlers. It wasn’t long before the new arrivals were dissatisfied with the Mexican governmental system and in 1835 they rebelled, calling their newly established governing body the Republic of Texas. Again, as was apparent during the Revolutionary War and subsequent battles since, Indian involvement with the rebellion was feared by both sides. In February of 1836, Sam Houston met with Chief Bowles and both agreed that the Indians could remain on their land in exchange for their neutrality during the revolution. Unfortunately, the treaty between Houston and Bowles was never ratified. Though Houston, who was later elected president of the Republic of Texas in September of 1836, was an advocate for peaceable ties with the Indians, his successor Mirabeau Lamar, was vehemently opposed to rights for Native Americans. Lamar encouraged the settling of lands within designated native lands, inciting conflict and giving him the pretext he had needed to petition the government regarding the removal of all Indian tribes within Texas. Many tribes, including the Kickapoo, fled either into Indian Territory to the northwest or further south into Mexico.

South of the Border

The first mention of a Kickapoo group in Mexico was in 1839, along with Cherokee, Delaware, and Caddoes. Beginning in June, small parties consisting of approximately 80 warriors from several tribes were seen entering the city of Matamoros from eastern Texas, all of whom were mustered into the Mexican military as a preventative measure against Indian attack. On June 27, 1850, Wild Cat, the Seminole chief, also in charge of the Kickapoo and Seminole groups, signed an agreement with the Inspector General of the Eastern military colonies, Atoio Maria Juaregui. Under this agreement, the new colonists received 70,000 acres of land, were instructed to obey the laws of the area in which they were settled, maintain good relations with the U.S., muster warriors for Mexico when needed, and “prevent, by all means possible, the Comanches and other barbarous tribes from their incursions through the area” (Latorre 1976:13). Most importantly, however, an additional clause in the agreement stated that it was not required of the new settlers to change their habits or customs, a point not forgotten by the Kickapoo. This agreement also established the Kickapoo as a sovereign nation within Mexico (Ritzenthaler and Peterson 1954). Shortly thereafter, many of the 500 Kickapoo in Mexico moved back into the United States through the border town of Eagle Pass, Texas. Only Chief Papicua with nine men, seven women and four children remained in Mexican territory. They, and some remaining Seminole, were moved to Hacienda El Nacimiento, more inland than originally agreed upon, in hopes of curbing the efforts of slave traders to acquire victims near the Mexican border.

During the U.S. Civil War, the Kickapoo residing in the Indian Territory of Kansas and Oklahoma were petitioned by the Northern and later the Southern armies to join the fight. Many made their way down to Mexico in hopes of remaining neutral during the fighting, but when they arrived in Mexico they were petitioned by the Mexican government to enlist in the military as part of the 1850 agreement signed by Chief Wild Cat. They refused to do so. In 1865, all of the remaining Kickapoo, with the exception of those residing in Kansas, were located in Mexico, and in 1866, they were allocated land outside of Muzquiz by President Benito Juarez (Ritzenthaler and Peterson 1954; Latorre 1976). In 1871, Kansas Kickapoo leaders attempted to persuade the Mexican Kickapoo to return to the United States, but they were not permitted to contact them. Though met with hostility by many Americans along the Texas-Mexico border, the Mexicans viewed the Kickapoo and Seminole as “civilized” Native Americans, keeping out the more hostile Native American groups that attempted to raid their presidios and pueblos. A peaceful way of life did not find the Mexican Kickapoo until 1920. Only then did they begin to farm and raise stock, “hoping the Mexicans and all others would leave them alone in their isolated village” (Latorre 1976:25).

The long-anticipated seclusion of the Mexican Kickapoo lasted just over two decades. The mid-forties brought drought, compounded by the tapping of the Kickapoo reservoir by a smelting company, as well as increased fencing by ranchers, tick-control problems, and a threshing machine. Slowly at first, and in order to provide for their families, a few Kickapoo at a time made their way to Eagle Pass, Texas, the largest border town closest to the village, in hopes of finding employment on farms elsewhere. By the time the Latorres reached the village in 1960, “98 percent or more of the Kickapoo left each April to spread from California to New York as migrant workers, returning to their village in the late fall” (1976:25).

Recent History

Migrant work continues to be a source of income for the Mexican Kickapoo. Up until the mid 1950s, the Mexican Kickapoo wishing to enter the U.S. were allowed to enter the country by showing a copy of a document of safe-conduct, issued to the Kickapoo tribe in 1832 at Fort Dearborn in Illinois. Years in Mexico however made it increasingly difficult to identify those of Native American descent from those of strictly Mexican descent, due to slight assimilation through marriage and language. This was compounded by the fact that some Mexicans used copies of the original safe-conduct to enter the United States. In response, the Mexican Kickapoo were then issued cards by immigration services of the United States reading: “Member of the Kickapoo Indian tribe, pending clarification of the status of Congress.”

After crossing into the U.S. during the harvest months, the tribe would camp under the international bridge at Eagle Pass, setting up a temporary “shantytown” from which they could find work in California, Colorado or another western state. Beginning in the late 1970s this migrant band was recognized as the “Traditional Kickapoo Tribe of Texas,” and in 1983 some of the band recognized as Texas Kickapoo were granted U.S. citizenship, culminating in a public ceremony in 1985 (Lawrence Journal-World 1985). These measures were carried out mainly in an effort to address the economic state of the tribe. The nomadic lifestyle of migrant workers, the low wages, and the fringe existence in two nations had taken its toll on the Mexican Kickapoo, and they live in a state of poverty, a situation made worse by a growing trend of substance abuse among Mexican Kickapoo youth. Without compromising tradition or culture, the Kickapoo still retain their traditional ceremonies, traveling back to the village near El Nacimiento during their New Year festivities to rebuild their traditional homes and conduct their sacred rites.

Currently there are four recognized bands of the original tribe first encountered in the Great Lakes: the Kickapoo Tribe of Indians of the Kickapoo Reservation in Kansas, the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma, the Traditional Kickapoo Tribe of Texas, and the band of Mexican Kickapoo still in Coahuila. This does not include the smaller groups that are scattered throughout the United States. In 1964, the Latorres counted 425 in the village but noted that it was difficult to say how many actually lived there because of the migratory work patterns. The 2000 Census recorded 3,401 people reporting Kickapoo as their native heritage (U.S. Census Bureau). This population count does not include those that were in Mexico during the Census recording.